La musica

dalla voce 'Banchieri' in Grove 2001

Musica sacra

Banchieri's sacred music includes psalms for the Offices (especially Vespers), masses and motets.

[salmi] The psalms are variously in relatively traditional polyphonic styles and in the more up-to-date concertato manner.

[messe] His 12 extant masses all reveal an adherence to the principles of the Council of Trent. The texts are clearly presented with rather simple counterpoint and a great deal of chordal setting. Musically they demonstrate nearly all the styles of composition used in the early 17th century. There is some variation among the masses in the formal divisions of the Ordinary text, with most variety appearing in the Credo; all but three of the masses substitute a motet for the Benedictus.

[motteti] Banchieri's other published motets appear not only under that designation but on the title-pages of later volumes in particular as 'concerti', 'pensieri' and 'dialoghi'. They include polyphonic pieces for two four-part choirs (Concerti ecclesiastici, 1595, including one of the earliest appearances of a separate instrumental bass part), duets with continuo (Dialoghi, concerti, sinfonie, e canzoni) and monodic pieces (Terzo libro di nuovi pensieri ecclesiastici, 1613).

Organ masses and other liturgical and non-liturgical works for organ are found in various editions of L'organo suonarino (1605).

Musica profana

Although there is evidence that some early pieces are lost, Banchieri acknowledged in his own numbering of his works only the 12 secular volumes that survive. He seems to have written most of the texts himself and made some use of dialect in them.

[canzonette] These volumes include six books of canzonettas for three voices, each containing some 20 textually related pieces which often employ the plots of the commedia dell'arte. Among these is his most famous, widely performed and frequently published work, La pazzia senile (1598), based on the amorous adventures of the commedia dell'arte character Pantaloon. This is a madrigal comedy in the Vecchi tradition, and two of the other three-voice books belong to this genre, Il metamorfosi musicale (1601) and Prudenza giovenile (1607) (called Saviezza giovenile in its second edition).

[madrigali] The other six books, which include comparable entertainment works, are basically for five voices (though they contain a few for smaller forces); the individual pieces in the earlier collections are called madrigals. The last three books include a continuo: the music becomes less polyphonic as groups of fewer than five voices are employed in conjunction with the bass, which takes on an individual role and displays melodic characteristics of its own. The subtitles of these last three books offer some clue to the changing character of the music; as well as vocal pieces Il virtuoso ritrovo academico (1626) contains canzonas specifically for violins. The subject matter of these 12 collections, especially those for five voices, also includes the pastoral stories of Greek mythology (Il zabaione musicale, 1604) and the presentation of a single idea (in Vivezze di flora e primavera, 1622, each madrigal adds to the general idea of nature reawakening in spring).

[strumentale] Banchieri was also a pioneer in writing canzonas and fantasias for instrumental ensemble, which are evidently original works for the medium and not arrangements of vocal pieces.

Madrigali II (1605, 1626)

La barca di Venezia per Padova

Con questo titolo Banchieri nel 1605 pubblica quella che sarà la sua seconda e più fortunata raccolta di madrigali, detta op. xii. Il frontespizio recita:

Barca di Venezia per Padova. Dentrovi la nuova mescolanza di Adriano Banchieri, libro secondo de' madrigali a 5 voci, nuovamente composti e dati in luce. Opera duodecima — In Venetia, appresso Ricciardo Amadino, mdcv.

La raccolta sarà ristampata nel 1626 con lievi modifiche e l'aggiunta del continuo:

Barca di Venezia per Padova. Dilettevoli madrigali a cinque voci di Adriano Banchieri, nuovamente in questa seconda impressione stoppata, impegolata e aggiuntovi il basso continuo (piacendo) per lo spinetto o chittarrone. Con privilegio — Stampa del Gardano, in Venetia mdcxxiii.

Madrigali III (1608)

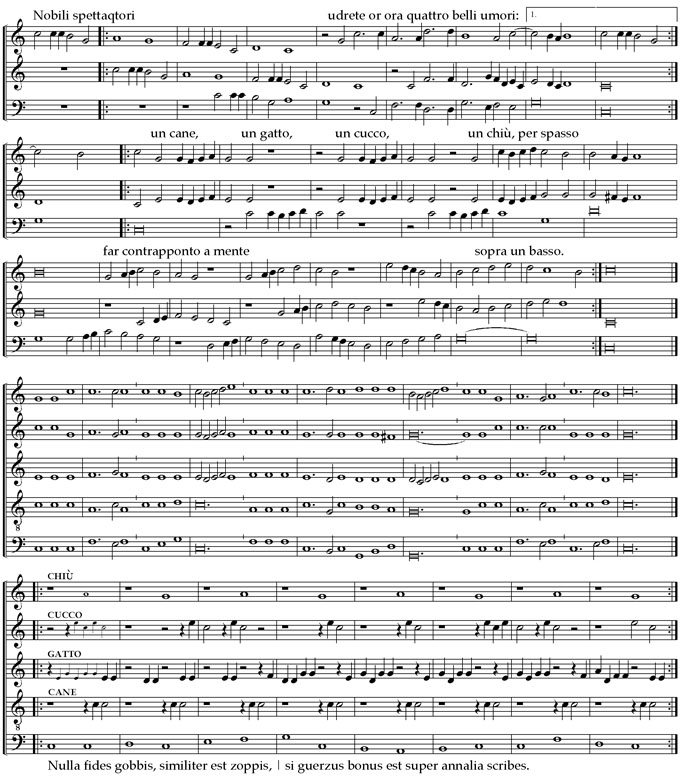

Cappricciata e Contrappunto bestiale alla mente

Si tratta di due brani della sua terza raccolta di madrigali a cinque voci, pubblicata nel 1608 come Festino del giovedì grasso, in genere sempre eseguiti in coppia perché entrambi legati allo stesso soggetto.

La musica si presenta in tre sezioni, la Capricciata a tre parti che introduce il Contrappunto a cinque:

|

|

La seconda sezione, in tripla, che introduce il Contrappunto ha

un passaggio che può essere efficacemente eseguito in emiolia, come

propongono i 'Suonatori della gioisa marca' diretti da Diego Fasolis (Naxos

1997). ![]()

«Alla mente» significa improvvisato, a sottolinearne la semplicità. I versi che canta il basso riprendono una frase tratta dal Baldus di Teofilo Folengo (1491-1594):

Marrangonus

ait: «Sic est, vult forte negare?

O Deus, a guerzis, zoppis, gobbisque

cavendum est».

Respondet Cingar: «Parlasti vera,

magister,

nulla fides gobbis; mancum, mihi credite, zoppis;

si sguerzus

bonus est inter miracula scribam». [viii, 330-334]